If you've been following the previous parts of this series, you've already grasped the foundations: how capital works, why buffers matter, and what makes a bank resilient. Now it's time to connect all those puzzle pieces.

⚠️ Warning: this might just fry your brain. We're entering acronym territory — CET1, TLAC, LCR, NSFR, G-SIB, CCyB — and they're coming in hot. But don’t worry: I’ve included a full list of abbreviations at the end of the article so you won’t get lost.

And yes, we’ll wrap things up with a real-life deep dive into J.P. Morgan, one of the biggest banks in the world.

Grab a coffee, relax, and let’s jump in!

Basel III

Let’s start our journey in Basel, a city in the North of Swiss. No worries, we didn’t turn into a travel page all of a sudden. When it comes to finance, we’re more interested in the Basel Committe on Banking Supervision, the organisation that draften the Basel Accords. Now, what exactly is this all about?

Rules. And not just rules for everyone. Rules for financial institutions specifically.

You see, as I’ve mentioned a couple of times already, is that financial institutions are rather big and impactful. So impactful that the default of a large player would cause a shockwave through the economy. They pose a so-called systemic risk. Therefore, stricter rules - especially when it comes to capital - were set up for these banks. These rules are solidified in the Basel Accords. They started out rather easy, with minimal requirements of capital in Basel I, later extended with rules regarding supervision and operational risks in Basel II. Only after 2008 - you know, the Great Financial Crisis - the full rulebook was drafted, and ultimately approved in Basel III.

In summary, Basel III consists of three pillars that were already introduced before: (1) Minimum capital requirements, (2) Supervisor review and (3) Market discipline. For us, the most important one is the first one, minimum capital requirements.

Now, you might ask: “Why does this matter when looking at the value of a bank?”. That’s exactly what the next parts will be describing!

Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1)

The first - and most essential - layer of protection is the so-called CET1 Capital. The purpose of this capital is to absorb losses in times of economic stress. Preferably, it’s not touched at all. It acts as a life saver for banks. This CET1 capital consists out of two components: (1) the Minimum CET1 requirement of 4,5% and (2) the Capital Conservation Buffer of 2,5%. There are differences in consequences if banks go below both thresholds, but we’ll not dig too deep into these.

So, a CET1 capital buffer of 7% (4,5% + 2,5%). Now, two important questions need to be answered: (1) “percentage of what?”, and (2) what counts as CET1 capital? The first one is - again, I know - specific to financial institutions and their operational risks. Buffers are measured against Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA). The concept is not that hard when illustrated with an example. Take two loans, one extremely risky with a very low chance of being paid back, while the one is a safe asset-backed mortgage loan, both of $100,000. When looking at the RWA, the value of both loans will be weighted according to their risk. In our example, the risky one would count for 100%, so it would have a value of $100,000. The second one, on the other hand, would only count for 20%, as it’s a safe loan. Hence, the value in the RWA would only remain $20,000. The lower the RWA, the less CET1 instruments are needed to get a ratio of 7%. You see, operational risks are included in these ratios. Safer banks will attain them quicker, while risky banks will have to cough up some more buffers.

There are a couple of criteria to be eligible as CET1 capital, but think about equity, retained earnings, other reserves,… As said in the previous part, this type of capital is the most expensive from a shareholder’s perspective. Hence, the less risk a bank takes, the less expensive capital it will have to bring to the table, and vice versa.

Additional Buffers

Banks need to hold some additional buffers as well. These buffers are used as a first protective layer to absorb losses, and to avoid getting into this minimal buffers. However, these buffers are composed out of CET1 capital as well. First of all, some banks are required to hold a so-called G-SIB buffer. A what? A Globally Systemic Important Bank buffer. In other words, the concept of Too Big Too Fail doesn’t exist anymore. It held in 2008, but we’ve learned a lot since then…

The G-SIB buffer ranges between 0% - 3,5%, depending upon the bank’s size. Banks are put into different buckets, calculated on a bunch of criteria. To give you an idea of how the distribution looks like, let me show you the buckets for 2024, provided by the Financial Stability Board - there were 29 G-SIBS in November 2024, so not all are on there:

Another buffer that can added is the so-called Countercyclical buffer (CCyB). The purpose of this buffer is to act - you could’ve guessed it - countercyclical. You see, banks are pretty pro-cyclical in nature: when the economy booms, everyone wants to borrow money, and when it crashes, everyone stays away from banks as far as possible. Hence, an economic crisis fuels a bank crisis and vice versa. The solution? A Countercyclical buffer. The concept is rather simple: in good times, the buffer is imposed. In bad times, the buffer is released. The result? Absorbing unexpected losses:

Additionally, banks need to have so-called Tier 2 capital. This is considered capital of less quality, and it serves again - take a guess - as a buffer against unexpected losses. In total, that is CET1 + Tier 2 capital, the minimal buffer should be 8% of RWAs.

Finally, there is another ratio called the Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC). Remember the Convertible Contingent Bonds (CoCos) from the previous part? Well, these come in here. The moment a bank is too close to failure, these bonds are converted into equity, thickening the capital buffers the banks can use. The process looks - in a very simplified way - like this:

Liquidity Ratios

Next to all these, banks need to fulfill in terms of liquidity. Two ratios are used to measure this: Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR).

The LCR measures the capability of a bank to withstand 30 days of heavy cash outflows. Or, in other words, a bank run. With certain models, an outflow percentage of different forms of funding is calculated, for example unstable deposits have an outflow of 10% over 30 days. This might sound not that much, but for a bank that’s holding trillions in liabilities, it can count. This is all summed up - I’ll leave out the details for now - and needs to be covered. By what? High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA). Again, the less high-quality and the less liquid, the more of a haircut - or discount - on these assets is taken. For example, cash counts for 100%, while high-quality corporate bonds get a cut of 15%, leaving 85% of the actual value. When is the test passed? Simple: the bank needs to achieve a ratio of at least 100%. Or, for the nerds among you:

HQLA / Cash Outflows >= 100%

The second ratio, the NSFR, measures how assets are financed. More precisely, how illiquid assets are funded. You see, it’s all about measuring risk. As a bank, you want to avoid at all costs that the funding dissappears, but the assets cannot be sold. Caught with your pants down. Hence, illiquid assets should be funded by stable capital, such as regulatory capital, sticky deposits (term deposits, for example) and long-term debt. Again, banks need to achieve a ratio of 100% to pass. Still some nerds in the room?

Illiquid Assets / Stable Funding >= 100%

Of course, as this is such a regulated space, additional ratios have been created. However, as I’m (still) not an expert, and I don’t want to bore you with slight differences between ratios, let’s say we covered the most important ones. That means there’s only one thing to do now: from the theory to real-life… Let’s take a sneak-peek at how J.P. Morgan is performing!

Capital Buffers At J.P. Morgan

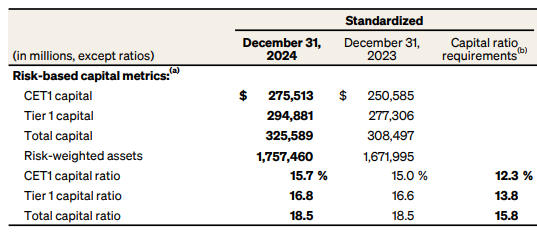

As you can see, the CET1, and Total capital ratio of J.P. Morgan have been comfortably above the minimum requirements for 2024. As you might have noticed, J.P. Morgan is the only bank in bucket 4 for the G-SIB buffers, giving them an additional requirement of 2,5% in CET1 ratio. 12,3% is rather high, but no risks can be taken with a bank as systemic as JPM.

The (average) liquidity ratio has been good as well at 113%, passing JPM with ease. For the NSFR, JPM refers to the additional report on this - yes, banks have a whole additional report on capital requirements - but it assures to achieve at least 100% as well. Very good. Very nice.

Finally, here’s the TLAC-ratio. As you can see, JPM scores another three-pointer with their TLAC as well. Easy pass. The LTD is a ratio we’ll not discuss, as it would take us to deep into the banking world. As your brain is probably quite fried by now, let’s que the final comments…

Closing Remarks

We’ve covered a lot in this piece: from capital layers and systemic buffers to liquidity requirements and JPMorgan’s real-life ratios. If your head’s spinning a bit, that’s completely normal. This is the heart of modern bank regulation, and while it’s dense, it’s crucial for understanding what makes a bank resilient… or vulnerable.

But we’re not done yet.

In the final part next week, we’ll shift gears from regulation to valuation. How do you translate all of this - CET1, TLAC, LCR, NSFR - into something that actually affects how you value a bank? That’s where we’re headed.

In the meantime, we’ve got another article coming your way this Sunday on a different but equally sharp topic, so if you haven’t already, make sure to subscribe to stay in the loop.

Thanks for reading — and see you soon.

Acronyms

Basel III

Third Basel Accord

BCBS

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

CET1

Common Equity Tier 1

CCB

Capital Conservation Buffer

RWA

Risk-Weighted Assets

G-SIB

Global Systemically Important Bank

CCyB

Countercyclical Capital Buffer

Tier 2

Tier 2 Capital

TLAC

Total Loss Absorbing Capacity

CoCo

Contingent Convertible Bond

LCR

Liquidity Coverage Ratio

NSFR

Net Stable Funding Ratio

HQLA

High-Quality Liquid Assets

📢 What’s the most surprising thing you learned about bank regulation? Drop your thoughts or questions in the comments!

🔔 Enjoying the series? Hit subscribe so you don’t miss next week’s deep dive into bank valuation.

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

Our Recent Free Posts

A Valuation Framework for Financial Institutions - Part IV

In Part III, we explored J.P. Morgan’s asset mix—how its loans, securities and trading positions drive returns and profitability. Today, we shift our focus to the flip side of the ledger: liabilities. We’ll conduct a deep dive into how deposits, interbank and central-bank borrowings, trading and operational payables, long-term debt and equity together f…

A Valuation Framework for Financial Institutions - Part III

Last week, we dove into the income statement of J.P. Morgan, exploring the key figures that drive profitability. This week, we shift gears to look at the assets — and, perhaps even more importantly, the returns generated on those assets. The split between assets and liabilities is essential, as each has unique characteristics that are crucial to underst…