⏳ Quick Reminder: Last Chance for Discount!

Our early supporter discount on the premium subscription ends July 1st. If you’ve been considering joining, now’s the time to lock in 60% discount.

Banks. Often called “greedy” or “reckless” - especially since 2008. No one still is suprised when they’re involved in scandals. Or worse, when they get away with it.

And still, banks remain the center of capitalism. About 80% (!) of people worldwide have a bank account or access to a financial institution via the internet, according to World Bank Group. That’s slightly higher than the people that use the internet worldwide. It’s clear, banks are among the most used services worldwide, and the numbers are only increasing.

“Why would I care?”, I can hear you thinking already, “I’m not interested in investing in a bank”. A fair point, can’t argue with that. However, the purpose of this (mini-)series is not to convince you into buying shares.

Rather, the goal is understanding the mechanisms.

Think about it this way: banks are the heart of an economy. Just like a heart pumps blood from one part of your body to another, banks “pump” money from one part in the economy into the other. Just like a healthy heart is key to your body, so are banks to the economy. Most companies - and most people for that matter - come in contact with a bank at one point or another. Loans, deposits, investments, the economy is full of these products.

Again, I’m not expecting that you go out and buy as many banks as possible. I do believe, however, that understanding financial institutions can dramatically help you to better understand the economy. In addition, understanding the business models of banks expands your valuation skills, as it forces you to look at companies from another perspective. In short, I believe it’s worth writing a series on. That said, feel free to counter me on that by leaving a comment or sending us a message - we’re always curious how our readers look at the topics we pick!

Anyway, enough with the introduction. Grab a coffee, sit back, and enjoy this first part on financial institutions.

Background

The first banking-like systems date back to ancient Athens, according to this paper. The “bankers” back then provided money exchange services and loans on the market. The system has always been build on the same commodity: trust. Already back then, lenders that failed to meet their obligations suffered reputational damage and were often excluded from the marketplace.

The first “real” banks - offering the possibility to deposit - arose in Italy, Florence. Florentine flourished because of its succesful merchants, who had to store their money somewhere at some point. Hence, the origin of the “classic” banker.

Over the years banks have kept on developing, facing the fundamental issues they still have today. Questions like “How to handle risk properly?” and “What assets can a bank hold?” were as relevant over time as they are today. However, technologies and regulations have drastically changed, shaping banking into what it is today.

Today, a handful of banks dominate the financial landscape. The biggest in the US - globally recognized names - are J.P. Morgan, Bank of America and Citigroup, holding respectively about $4,2 trillion, $3,3 trillion and $2,4 trillion in assets. Yep, that’s trillion with a T. For comparison, the GDP of Canada was about $2,14 trillion in 2023. In Europe, BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole and Banco Santander complete the top three. Each of them holds respectively about $2,6 trillion, $2,5 trillion and $2 trillion in assets. Smaller than US banks, but still an enormous amount of money.

To understand how banks can become so important, let’s take a look at their business model.

Business Model

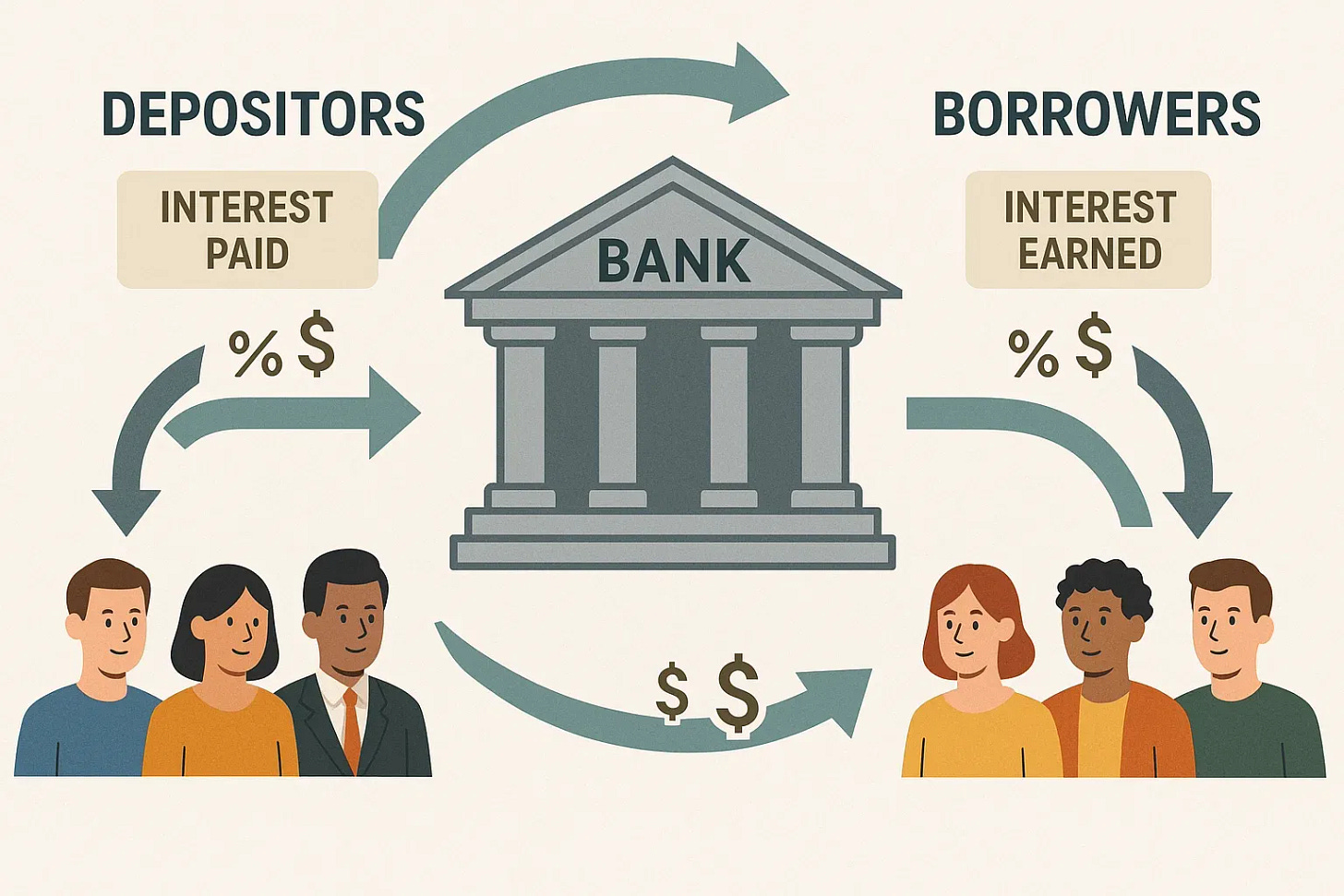

The business model of a bank is not what you would call normal. In fact, banks sell and buy a very specific - but highly in-demand - product: capital. In essence, banks act as nothing more than middlemen. People who have excess capital can store it in a bank, or - the more familiar term - deposit into a bank. People and companies that are short in capital can get it from the bank: loans. Therefore, banks make sure that capital is allocated from where it is not needed to where it is needed, as intermediaries. And, as many things in life, this does not come for free. Deposits - capital provided to banks - are paid for in the form of interest by the bank itself. On the other side, loans - capital provided by banks - are paid for in the form of interests by the borrowers.

Now, I know that in practice it’s not that simple. Over the last decades, financial institutions started to do a whole lot more than simply allocating capital. However, in essence, this is the main purpose of commercial banks.

The difference between interests paid out and those received is the profit a bank makes. This also implies that banks’ profits are closely related to the rates set by the central banks - something we’ll surely come back to in a next part of this series. It also implies that the financial income and expenses on a regular income statement become the operational income and expenses for banks. As you can see, when approaching capital as the “product” a bank sells, it becomes a more regular business model.

Obviously, there are still some differences in how a valuation would be performed due to this different business model.

Differences With Non-Financial Corporations

The main differences stem from two facts that we already mentioned: (1) only a handful of banks has the main share of the market, and (2) they operate with a different business model.

First of all, banks are very sensitive to interest rates. Later, we’ll see that interest rate increases or decreases also have a slightly different effect, creating (less) favorable circumstances. This implies that decisions concerning monetary policy have a direct impact.

A direct consequence of their business model is the difference in income statements. Banks report in a slightly different way because what financial expenses are for other companies, become operational profit for financial institutions.

Secondly, banks are very closely monitored, and need to comply with a lot of regulation. Due to the fact that banks have such a systemic impact - bankruptcy for an important financial institution often causes a shockwave through the economy - they need to fulfill certain standards.

Lastly, banks can create capital out of nothing. This is a very important caveat to the business model. For non-financial companies, the input is often related to the output. When doubling the input of resources - raw materials, for example - a non-financial company can roughly double its output - not taking into account scales of economies. In the case of banks, an additional input can lead to a output 10x higher. Leverage. Banks can - and certainly will - use it. Something very unique which we’ll certainly come back too.

Closing Remarks

As we wrap up Part I, let’s take stock of what we’ve uncovered so far.

We’ve challenged the oversimplified narrative of banks as merely “greedy” or “reckless” by taking a step back to understand how they actually function. From their origins in ancient marketplaces to today’s trillion-dollar balance sheets, we’ve seen that banks are not just institutions—they’re the circulatory system of the modern economy. Their business model, built around capital allocation, fundamentally differs from most companies. It’s a model that hinges on interest rate dynamics, regulatory pressure, and leverage—factors that make them unique, complex, and influential.

Most importantly, we’ve highlighted several key differences between financial institutions and other companies:

Capital is both their product and their raw material

Profitability is driven by interest spreads, not unit sales

Their income statements and regulatory obligations look very different

And yes—through leverage, banks can quite literally create money

If you’ve ever wondered why bank stocks are valued differently, or why central bank decisions shake financial markets to their core, this foundational understanding will serve you well.

In Part II, we’ll take a closer look at how to value a bank, what metrics really matter (hint: it's not just P/E), and how to think about risk in a leveraged financial institution. Even if you never plan to invest in a bank, understanding their role can sharpen your thinking on the broader economy and markets.

Curious? Then I’ll see you in Part II.

📢 What do you think? Are banks interesting enough to write a series about? Let us know in the comments!

🔔 Make sure to subscribe! It’s free and you receive all our articles directly in your mailbox!

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

Our Recent Posts

Value At A High Cost

Last week, we unpacked the backstories of Equinix and Digital Realty Trust: our two data center REITs caught in the analytical spotlight. But every good story needs a strong ending, and in finance, that means valuation. We’ve got the narrative, but does the math back it up?