“Gold and silver are money, everything else is credit"

- J.P. Morgan, 1912 -

Lately, the markets have been taking a beating, with the S&P 500 down 7.43%. Naturally, this has triggered a flood of articles warning us about "why the market is overvalued" or "the next big crisis." Every time stocks drop, the doom-and-gloom headlines start rolling in. But here’s the thing—market downturns don’t just bring risk; they also bring opportunity.

Still, after reading one too many apocalyptic takes, I started thinking: why not take a step back? Instead of obsessing over what might cause the next crisis, let’s take a deep dive into one of the biggest financial meltdowns of modern history—the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008.

And so, here we are. A four (or maybe five) part series, depending on how deep we want to go. This first installment is all about setting the scene—laying out the perfect storm of factors that led to the 2008 collapse. Because trust me, this wasn’t just a sudden market panic. The groundwork was years in the making.

So grab a coffee (or something stronger, I won’t judge), and let’s start with one of the first dominoes that fell—the Dotcom Bubble.

The Dotcom Bubble

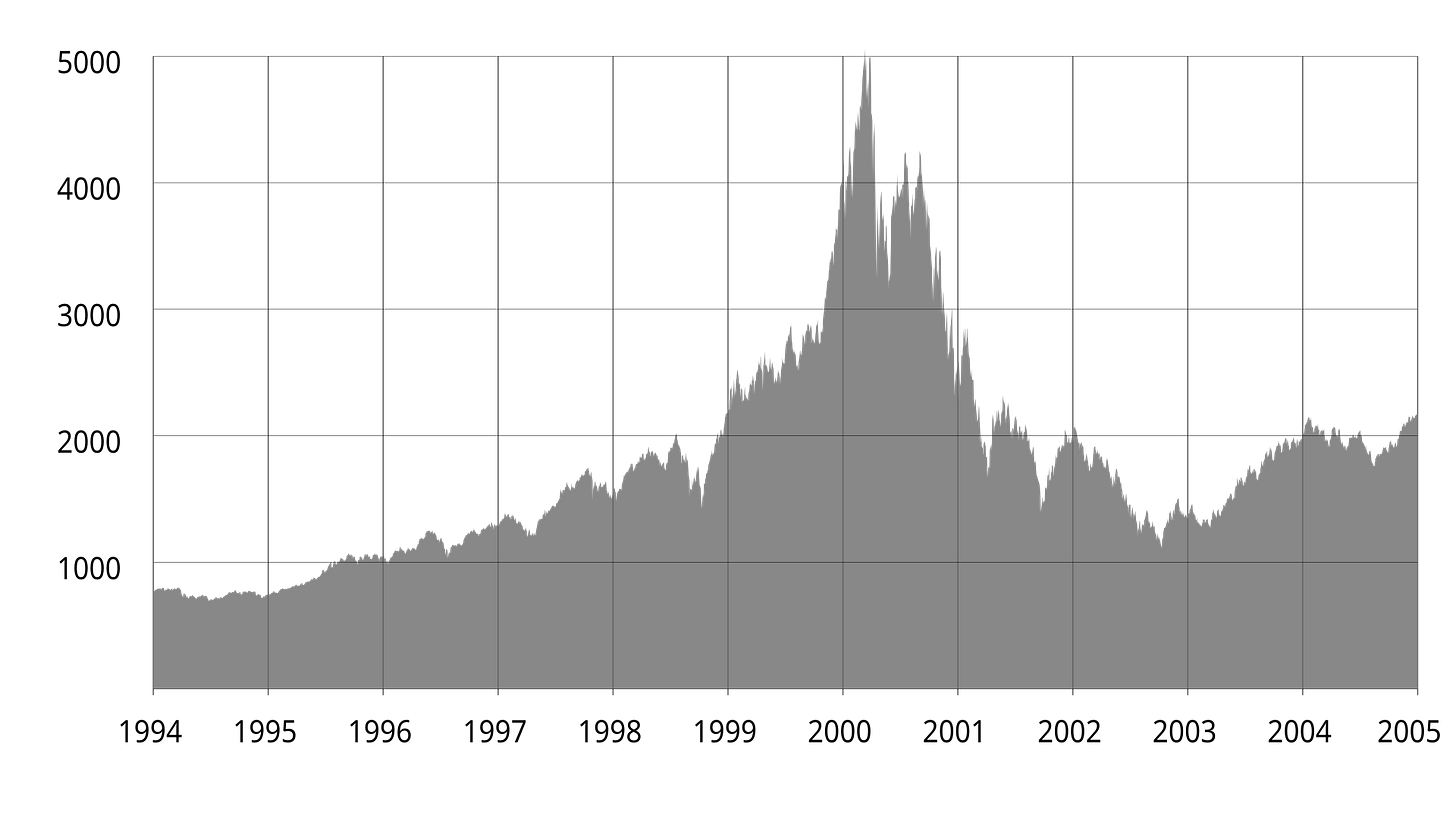

The first major player in this financial drama? The infamous Dotcom Bubble. For those who missed the madness, let me paint you a picture. It’s the late '90s, and the Nasdaq is on steroids, shooting up fivefold in just a few years. Why? Three magic letters: “.com”

You see, back in 1990, the Internet was born—a little invention you might have heard of. You know, the one that completely changed civilization as we know it. As the hype grew, companies realized something ridiculous: slap a “.com” onto your name, and bam! Your stock price skyrockets. It didn’t matter if you were selling actual tech or just staplers; if you had “.com” in your name, investors threw money at you like there was no tomorrow.

This led to a full-blown gold rush. Suddenly, every company and its grandma was IPO-ing overnight, soaring in value as investors blindly dumped their savings into anything remotely Internet-related. It was euphoric—until it wasn’t.

By 2001, reality crashed the party. Investors woke up and realized, “Wait… most of these companies don’t actually make money.” Panic ensued. Stocks were dumped en masse, triggering an unstoppable downward spiral. Over two brutal years (2000–2002), the Nasdaq plummeted by a staggering 76.81% (!!). Check out Graph I for a visual gut-punch:

Imagine buying at the peak… yikes. Naturally, all the fake “dotcom” firms went belly up, but some survivors—Amazon, Cisco—proved their worth and are still thriving titans today.

Of course, this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the Dotcom Bubble (maybe a deep dive article one day—hit that subscribe button if you're into this kind of thing). But for now, let’s see how this spectacular implosion helped pave the way for the GFC.

As you’d expect, the economy needed CPR after the bubble burst. That’s where the Federal Reserve stepped in, as shown in Figure II:

Econ 101 tells us that when the Fed slashes interest rates, it’s trying to jumpstart the economy. Banks can borrow more cheaply, making loans for consumers and businesses more accessible. More money, more investment, more growth—all good, right?

Well… not exactly.

Burned by tech stocks, investors weren’t about to make the same mistake twice. Much like a kid who gets burned by a hot stove, they steered clear of tech. But here’s the thing—they didn’t leave the market altogether. They just went looking for new ways to make money.

And oh boy, did they find them.

Some wandered into the world of derivatives, an asset class that is usually highly leveraged (read: financial rocket fuel). Investors started piling in with borrowed money, chasing returns. And guess who saw this coming? Warren Buffett. As early as 2003, the Oracle of Omaha warned that derivatives were a “time bomb” in his shareholder letter. Others took a safer route, and decided to invest in real estate because “housing prices only climb”. Boy, did they burn themselves even harder a few years later…

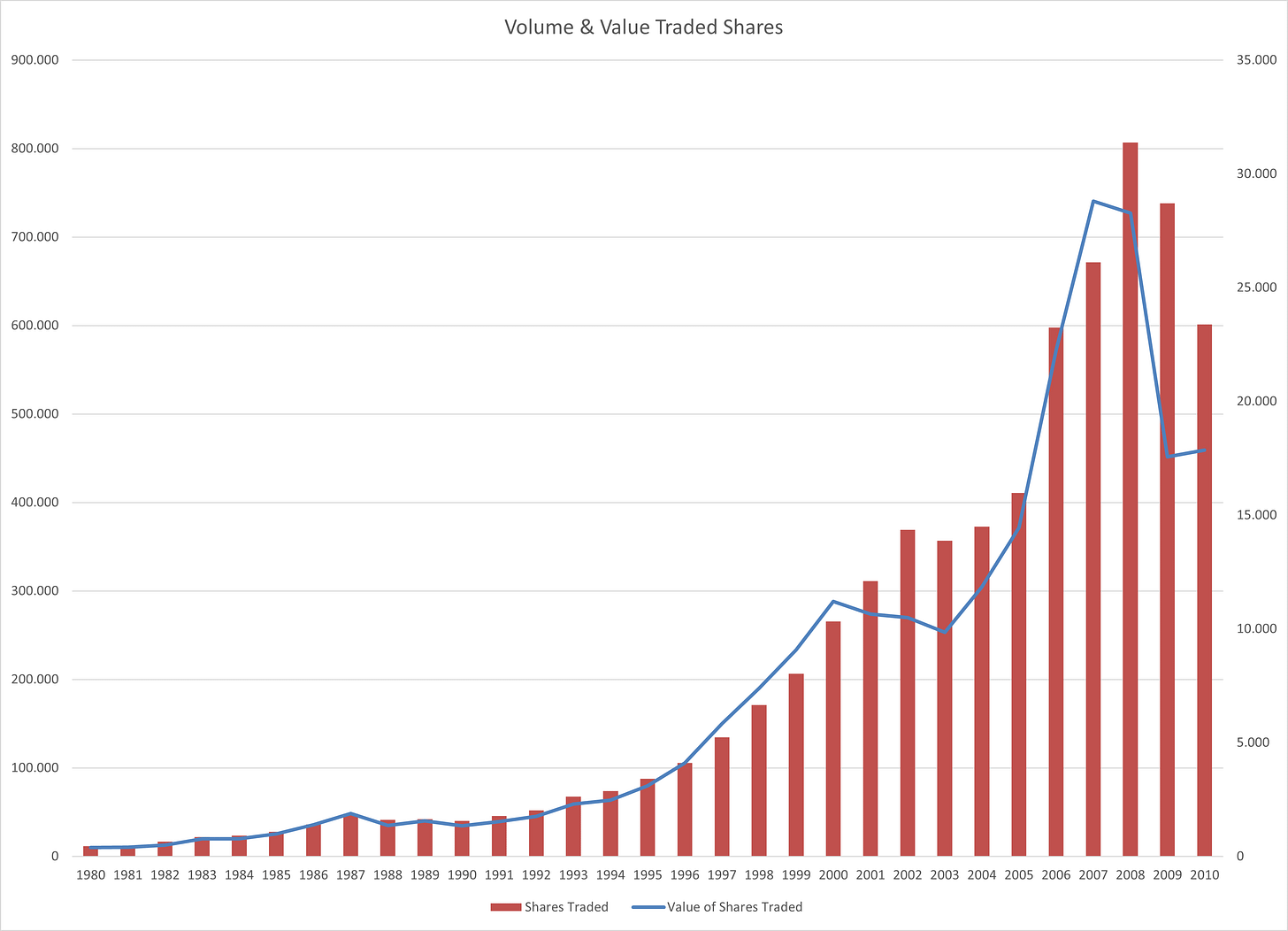

Ironically, the same Internet that fueled the Dotcom Bubble also made it easier than ever to trade these risky new assets. Take a look at Graph III, which tracks the surge in trading volume (left axis) and value (right axis) from 1980 to 2006 (source: U.S. Census). It’s not solid proof, but it sure supports the idea that investors were going all-in on high-yield plays.

More liquidity means more market swings—both ways. When things go well? They go REALLY well. But when they go south? They crash and burn even harder. A double-edged sword if there ever was one.

So, there you have it—the first major domino that led to 2008. Now, let’s talk about the next piece of the puzzle: shadow banking—which, let’s be honest, already sounds pretty shady…

Shadow Banking 101

Relax—shadow banks aren’t some secret cabal lurking in the dark alleys of Wall Street. In fact, they’re not even banks in the traditional sense. Why? Because real banks are bound by strict regulations—they have to play by the rules when it comes to liquidity, solvency, and all that good stuff. The biggest difference? Banks hold your deposits, while shadow banks don’t.

That also means shadow banks operate outside the direct control of regulators. Since they don’t hold consumer deposits, they fly under the radar, dodging the same scrutiny that traditional banks face. According to Investopedia, shadow banks are simply “financial intermediaries that fall outside the realm of traditional banking regulations.” Sounds vague? It’s actually closer than you think. We’re talking investment banks, brokerages, mortgage lenders, and even insurance companies—not exactly the boogeymen of finance, right?

At first glance—and probably because of the ominous name—you might think shadow banks are nothing but trouble. But hold on, they actually serve a real purpose in the economy.

"Sounds complicated," I hear you thinking. Bear with me.

(Regulated) banks lend money to people like you and me—or to businesses. The borrower takes on a debt, which is an asset for the bank. But here’s the catch: every loan carries risk—specifically, default risk (a.k.a. “Oops, I can’t pay you back.”).

And here’s where it gets even more interesting—banks engage in something called “maturity transformation.”

"Wait, what? That sounds terrifying."

Not really. It just means banks mostly hold long-term assets (mortgages, business loans, etc.) on their books. But where do they get the money to fund those loans? That’s right—your deposits.

And what do we all want? The ability to withdraw our money whenever we feel like it.

So, banks end up with long-term assets (mortgages) but short-term liabilities (deposits people can withdraw at will). That’s a maturity mismatch, which can cause problems if everyone suddenly wants their money back at the same time.

Now, enter shadow banks.

Shadow banks buy loans from traditional banks—mostly mortgages. This shifts the risk off the bank’s books and onto the shadow bank. The bank gets cash in hand, allowing it to keep lending to more customers.

Technically, the bank moves the loan to the liability side of its balance sheet because it now "owes" that mortgage to the financial intermediary. In practice, the bank still collects the loan payments and passes them to the shadow bank—minus a little cut, of course.

But here’s the kicker—if the borrower defaults, the shadow bank eats the loss, not the bank.

This system allows banks to lend endlessly, shifting risk away from their balance sheets and onto eager investors who think they’re buying golden money machines. To quote The Wolf of Wall Street:

“The park is open 24/7/365. Every decade. Every g*ddamn century. That’s it.”

But here’s the thing—when the whole system implodes, those same shadow banks are going to be right at the heart of the chaos. Keep this in mind for Part II next week, where things start getting really messy. You don’t want to miss it…

Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac (And Others)

Before we wrap up Part I, let’s take a moment to talk about some other key players in the Great Financial Crisis. I promise I’ll keep it short (or at least try).

Let’s start with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Who? No, they’re not the friendly folks who just moved in next door. In fact, they’re not even people.

Fannie Mae is short for Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA—if you say it fast, it kinda sounds like Fannie Mae). And Freddie Mac? That’s just the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, but someone got creative with the nickname.

These two institutions are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), which means they have a special relationship with Uncle Sam. But before 2008, they weren’t fully government-backed. I’ll let you guess where it went wrong…

Their job? Buying up tons of mortgages to provide liquidity in the housing market. Think of them as massive mortgage middlemen—they didn’t issue loans themselves, but they bought them from banks - similarly to shadow banks - bundled them into securities, and sold them to investors. The idea was to help more people buy homes while letting banks offload some of the risk.

Sounds great, right? Well… not quite.

The problem? Fannie and Freddie bet EVERYTHING on mortgages. Their entire business relied on the housing market staying strong. So when things started crumbling in 2008… so did they. As we’ll see later, their collapse had massive ripple effects across the financial system.

Laws are boring? Not these ones. Because a handful of key laws played a huge role in setting up the crisis. Let’s break down three of the big ones:

1. Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) – 1999

Back in 1933, after the Great Depression, the U.S. government decided banks needed to chill out. They passed a law (Glass-Steagall) that split up commercial and investment banking. That meant:

No using your deposits to fund risky investments.

No more banks gambling with people’s money.

Good idea, right?

Well… in 1999, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act reversed all of that. Suddenly, banks could do it all again—hold your deposits, make risky bets, and become too big to fail.

"Wait, so my bank can invest my money however they want?"

Yep. In theory, if they played it safe (think government bonds), no problem. But greed is a powerful drug. Once banks got a taste of high-risk, high-reward investments, things started to spiral.

2. Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) – 2000

This one flew under the radar, but its impact was huge.

The CFMA deregulated the derivatives market, which included two infamous financial products:

Credit Default Swaps (CDSs)

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

Don’t worry, we’ll get to those later. Just know this: derivatives + low interest rates + high liquidity = a ticking time bomb.

Warren Buffett called derivatives “financial weapons of mass destruction” in 2003. Should’ve listened to the man…

3. Alternative Mortgage Transaction Parity Act (AMTPA) – 1982

Before 1982, getting a mortgage was simple—you took out a loan with a fixed interest rate, meaning your monthly payments stayed the same for 20-30 years. No surprises. No tricks.

Then AMTPA came along and said:

“Hey banks, go wild. Get creative with your mortgage products.”

And boy, did they.

This law unleashed all kinds of “exotic” loans, like:

Balloon Payments – Pay almost nothing for years, then one massive lump sum at the end.

Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) – The interest rate changes every few years, tied to the Fed’s rates.

These ARMs were especially dangerous. Why? Because they started cheap, luring in tons of borrowers who thought they were getting a deal. But when rates shot up right before 2008, their mortgage payments skyrocketed—and many simply couldn’t afford them anymore.

Take a look back at Graph II (the Fed’s funds rate), and you’ll see exactly why this blew up in everyone’s face.

So, that’s it for the setup. We’ve covered:

How Fannie and Freddie loaded up on mortgage risk.

How deregulation let banks and investors run wild.

How exotic mortgages turned homebuyers into financial time bombs.

In Part II, we’ll dive into the main players and the dominoes that started falling one by one. Trust me, you don’t want to miss it.

Hit that like & subscribe button if you’re enjoying this breakdown! Part II is coming soon!

📢 I’d love to hear your thoughts - what’s your take on the Great Financial Crisis? Do you think history is repeating itself with today’s markets? Drop a comment below with your insights, feedback, or even just to say hi! 👇

🔔 Don’t Miss Out! If you’re enjoying our financial deep-dives, make sure to hit that subscribe button so you won’t miss Part I of our breakdown on Aris Water Solutions this Sunday!

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

Our Recent Posts

Market Structures & Their Impact On Economic Moats

Imagine strolling through a bustling outdoor market. Vendors are calling out their best deals, colorful fruit is piled high on wooden carts, and the air is filled with the smell of fresh bread and roasted coffee. As you weave through the crowd, something catches your attention - two different stalls selling the exact same apples, but at different prices…

Navigating the Waters: Analyzing Aris’s Strategic Landscape

Today, we’re wrapping up our qualitative deep dive into Aris. But don’t get too comfortable—this journey is far from over. Next week, we’ll roll up our sleeves and we will start to tackle the numbers. But before we dive into the world of data and calculations, let’s make sure we’ve got our story straight. After all, what’s the point of crunching numbers…