In Part III, we explored J.P. Morgan’s asset mix—how its loans, securities and trading positions drive returns and profitability. Today, we shift our focus to the flip side of the ledger: liabilities. We’ll conduct a deep dive into how deposits, interbank and central-bank borrowings, trading and operational payables, long-term debt and equity together fund over $3.6 trillion of assets. With these fundamentals in place, let’s turn to the nitty-gritty of bank funding.

Grab a coffee and join me as we unpack the layers of today’s banking backbone!

The Basics

Liabilities. The funding of a company. The same goes for banks. In Part III, I tackled assets and returns. Today, let’s take a look at an at least equal - maybe even more - interesting part of the balance sheets: liabilities. I have already shed some light on some of the liabilities, but today we’re going for a deep-dive. Before diving into too deep, let’s take a look at the basics:

As already mentioned a few times, deposits play a very important role on the liabilities side of a bank. There are a few types of deposits, of which Deposits on Demand - the ones that can be withdrawn at any point in time - are the most used. Furthermore, there are also the savings, on which the savings rate is slightly higher, and the term deposits - the ones that are committed for a short period to the bank. Together with Interbank and Central Bank Borrowing, these make up the short-term funding. Of course, Interbank and Central Bank Borrowing can be long-term as well, but usually - that is, in normal economic times - they’re not

Secondly, let’s take a look at capital. This is pretty straight-forward and pretty much the same as with non-financial firms. The biggest difference? That’s something to dissect in the next part of this series. Maybe one hint: banks are heavily monitored, and so is their capital. Anyway, more on this in the next part, so make sure to subscribe!

The last chunk of the liabilities consists out of bonds, at which we’ll take a deeper look. Remember for in the practical example: bonds are some sort of debt. You see, banks need a lot of capital to be able to (re)distribute it to the economy. To diversify the risks in terms of funding, different types of bonds are used. To give you a first idea on the different risks associated with the different bonds, here’s an overview of the so-called Seniority Ranking of Corporate Capital Structure:

Keep in mind that this is a general overview, but most firms don’t issue such a diversity of bonds. Let’s walk through. First of, there are the usual suspects: Senior Secured and Unsecured Bonds. If a bank defaults, these are the first ones to be repaid back to the borrower. After this, we have the Guaranteed and Insured Bonds, a little less safe.

Then there are the CoCos, or Convertible Contingent Bonds - a special type of bail-inable bonds. Let me quickly explain. Banks, and companies in general, prefer to issue bonds (debt) over shares (equity) if possible. Why? Simple. You pay your debt back, and you’re done. However, issuing equity lets investors share in the profits for the remainder of the firm’s existence. And here’s the kicker for banks: they need to have a certain capital buffer in order to be compliant. If the capital falls below this buffer, CoCos are automatically converted into equity, to refill this capital buffer. It’s an expensive form of funding for banks, but still preferred over issuing additional shares, because for healthy banks these CoCos behave like debt. Finally, there are the equity instruments such as preferred and common stocks - again usual suspects at any company. Additionally, there’s also the retained earnings, the most preferred form of equity.

These forms of funding also follow the simplest finance rule: the higher the risk, the higher the expected returns. Funding at the top - (un)secured bonds - requires less of a reward, translated into lower interest rates. Funding at the bottom, such as CoCos and equity, have a much higher expected return. How exactly banks determine what to issue when, we’ll analyze in the next part of this series, but this gives you a steady base of understanding of how a bank can be funded.

For the rest of this article, let’s dive into a real-life example. Continued from last week, I’ll shortly analyze the balance sheet of J.P. Morgan.

Measuring Risks

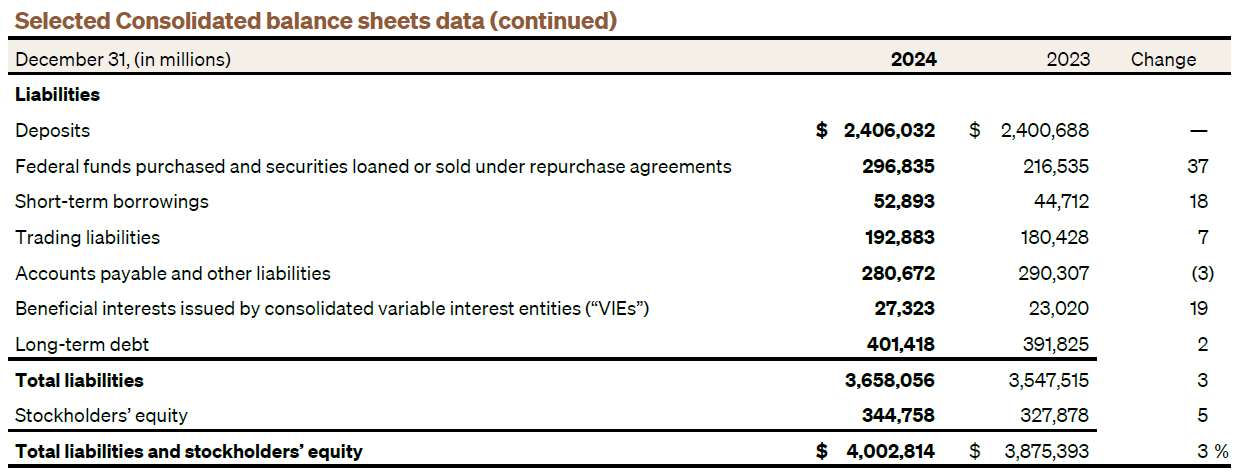

When analyzing the balance sheet of J.P. Morgan, it’s immediately clear that deposits - on demand, savings, and term - make up the bulk. Over 60% of funding comes from deposits, a relatively cheap form of debt. When looking at the next two lines, the Central Bank and Interbank borrowing shows up. About $350B of funding - or roughly a little under 10% - comes from loans provided by other banks and the Federal Reserve. The Trading, Accounts Payable, and VIEs liabilities consist of operational liabilities, such as funding of derivatives and - just like non-financial firms - liabilities to suppliers. To close of the debt part, there’s the long-term debt, which consists out of bonds with a higher maturity. Finally, coming in at a little under 10% - but still sufficient - there’s the stockholders equity. For a full, detailed breakdown, check out the Annual Report of 2024, but for now, I’ll stick to the high-level overview.

This serves as a basis for the next part, which will be a little more complicated and lengthy - so enjoy this shorter and simpler part. The purpose of the next part will be to look at how banks need to be protected in order to not be a systemic risk - a risk to the whole economy. Big players carry big responsibility, and should be moving very carefully through the economic landscape.

Closing Remarks

Today’s deep dive has shown that a bank’s funding stack is anchored by core deposits—demand, savings and term accounts—supplemented by interbank and repo lines, trading-related payables, long-dated bonds and, at the very bottom, equity. Grasping this liability mix is crucial for understanding funding costs, tenor risk and loss-absorption capacity.

Next week, we will build on these basics to examine how regulatory buffers and seniority rankings (from senior bonds to CoCos and equity) shape a bank’s true cost of capital.

If you’re a premium sub, make sure to don’t miss our special Sunday feature, where we’ll put our previous valuation insights into our final verdict on Givaudan.

See you then!

📢 Which liability category surprised you most? Core deposits, interbank borrowings or CoCos? Drop your thoughts below and join the conversation!

🔔 Enjoyed this deep dive? Hit subscribe so you never miss our weekly breakdowns and special features!

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

Our Recent Posts

A Valuation Framework for Financial Institutions - Part III

Last week, we dove into the income statement of J.P. Morgan, exploring the key figures that drive profitability. This week, we shift gears to look at the assets — and, perhaps even more importantly, the returns generated on those assets. The split between assets and liabilities is essential, as each has unique characteristics that are crucial to underst…

![[FULL ANALYSIS] -- Melexis](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!vC4Q!,w_280,h_280,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3040bec8-18f9-4650-9f28-d6676f341fe9_261x193.jpeg)