“You better cut the pizza in four pieces, because I'm not hungry enough to eat six.”

- Yogi Berra -

M&M? Pizza? Wait—did this just turn into a food blog? Relax, we’re not discussing snacks today (unless you’ve got a killer capital structure quote that can compete with food metaphors). What we are diving into is something just as essential—at least for finance nerds: the impact of capital structure. Or, to be more precise, whether capital structure even matters in the first place.

Hold up, let’s rewind a bit.

We’ve covered a lot in this blog, including company finances—how much debt they’re carrying, solvency ratios, all that fun stuff. Because, obviously, understanding a company’s financial health is important, right? Knowing how much of its assets are funded by debt? That’s key… right?

Well… depends on who you ask.

In 1958 (yes, over six decades ago), two economists—Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller—came up with a theory that flipped conventional wisdom on its head. The Modigliani-Miller Theorem (M&M, but no candy involved) argues that how a company is financed—debt or equity—doesn’t actually affect its total value. In other words, capital structure is irrelevant.

Sounds crazy, right? But, as always, the truth isn’t that black and white. There’s nuance, and the real-world application of this theory has a few twists. Since we kicked off with food, let’s close with a drink—grab a coffee, and let’s break it down!

M&M - Modgliani & Miller Theory

Let's rewind to 1958—an era when corporate finance was just finding its feet. The Modigliani-Miller (M&M) theory emerged like a bolt of lightning, shaking up the field with its bold claim that, under certain conditions, the way a firm finances itself doesn’t affect its overall value. Today, it remains a favorite of mine, not only because of its groundbreaking insight but also because it’s one of two “irrelevance” theories that M&M introduced (the other, dealing with dividend policy, might just sneak into your inbox if you’re subscribed!).

Here’s the basic idea: a company’s value is determined by its future cash flows, discounted back to the present—yes, you’ve heard this before. So, if a financial decision doesn’t change these cash flows, it won’t change the firm’s worth. Simple, right? But, of course, there’s a twist. M&M’s argument relies on a set of rather unrealistic assumptions: a frictionless world with no taxes, no transaction or bankruptcy costs, perfect information among all investors, and a magical world where everyone can borrow at the same rate. Even in 1958, these assumptions were a stretch—especially since, in reality, debt often comes with a sweet tax shield.

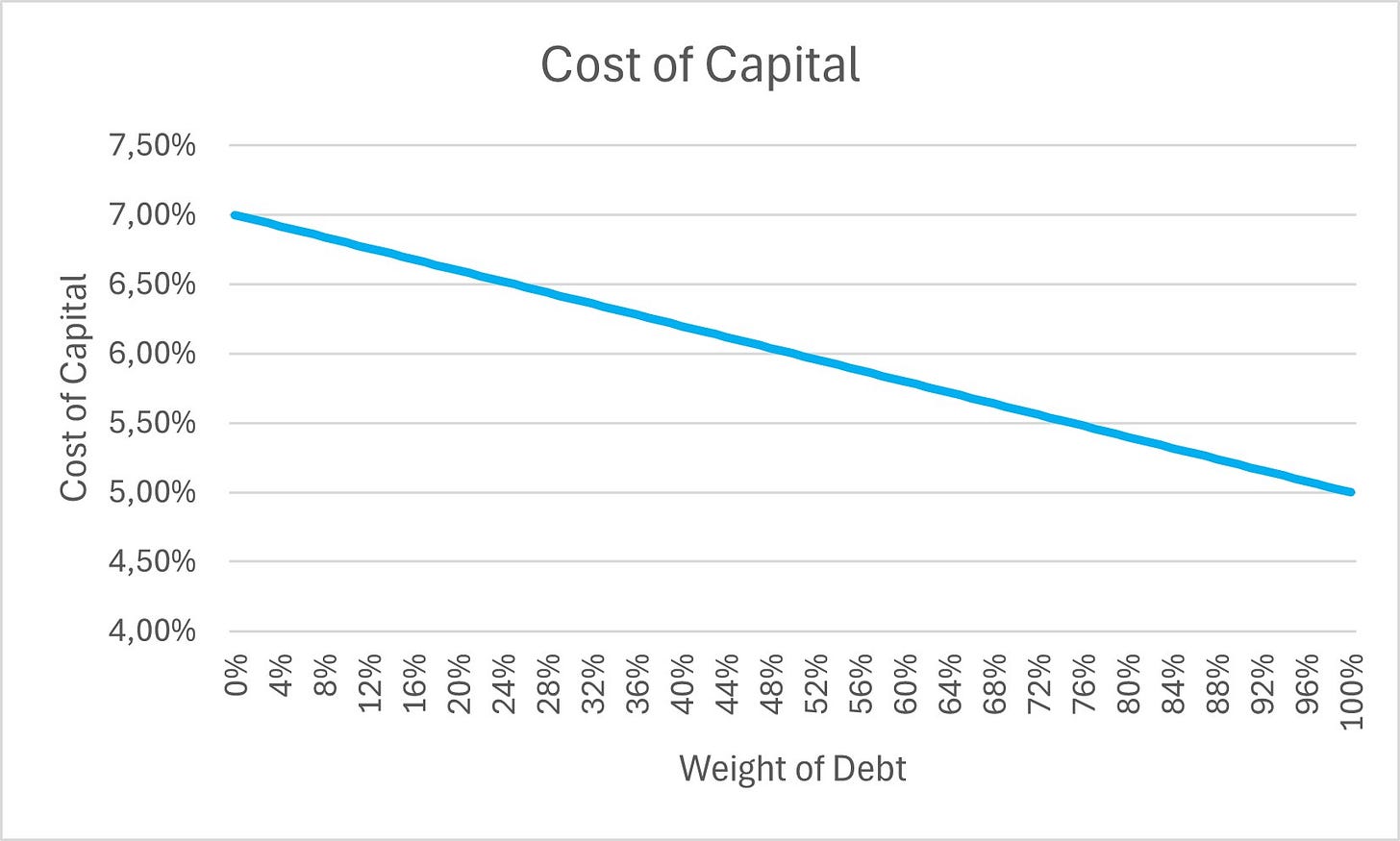

Now, let’s talk WACC—the Weighted Average Cost of Capital—for the finance buffs among us. WACC is just a blend of the cost of debt and the cost of equity. Imagine a firm with $100 million in debt at a 5% cost and $200 million in equity expecting a 7% return. Calculating the weighted costs for both debt and equity gives us 1.67% (5% * $100 million / $300 million) and 4.67% (7% * $200 million / $300 million). Adding up these weighted costs results in a WACC of about 6.3%. For the same costs (e.g. 5% and 7%), the cost of capital would be as follows for different combinations of debt and equity:

Now, if the firm swaps its balance sheet to $200 million in debt and $100 million in equity, you might think the lower weighted cost of debt would drive down the overall cost, as shown in Figure 1. But hold on—investors, ever alert, would demand a higher return on equity to match the increased risk, effectively neutralizing any initial benefit.

So, in the world of M&M, taking on more debt might seem like a clever hack to lower your overall cost of capital, but the rising risk adjusts the returns in such a way that the firm’s value remains unchanged. It’s a neat, if idealized, concept that still offers a lot to chew on—even when we start peeling back the unrealistic assumptions.

Back To Reality

So, what if we strip away the unrealistic assumptions that M&M originally made? Well, Modigliani and Miller did that too, and the result comes down to two key formulas—officially called propositions—that reshape the conversation around capital structure.

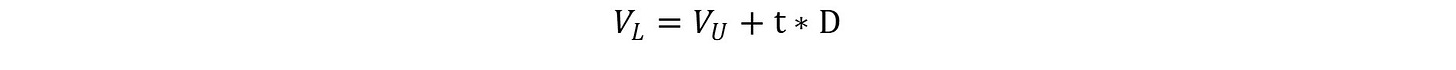

First, let’s start with Proposition I:

This tells us that the levered firm (V_L) is always worth more than the unlevered firm (V_U) by exactly the amount of the tax shield (tD). In simple terms: debt financing creates value because interest payments reduce taxable income. A cash flow boost thanks to Uncle Sam? Beautiful.

And if we set taxes to zero (t = 0%)? The value of a levered firm and an unlevered firm would be exactly the same—which is what M&M originally argued.

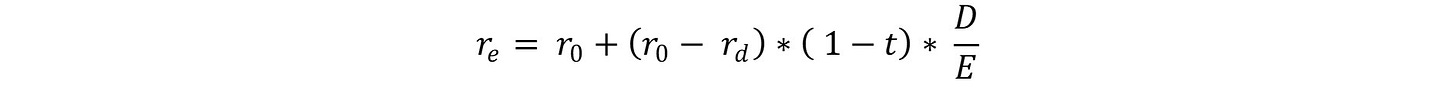

Now, onto Proposition II, which looks at the cost of equity when debt is introduced:

Here’s what matters:

Re is the cost of equity, and we can see that it increases as debt (D) increases. Makes sense, right? More debt = more financial risk = equity holders demand a higher return.

R0 is the cost of equity for a firm fully financed through equity (non-levered firm), and Rd is the cost of debt.

If taxes don’t exist (t = 0), the cost of equity rises in direct proportion to debt.

But with taxes, the effect is softened by the tax shield, making debt a little less scary.

In the extreme case where t = 100% (meaning interest is fully deductible), debt wouldn’t increase risk for equity holders at all, because the tax shield would completely offset it.

In other words: introducing taxes changes everything—and it’s exactly why debt plays a crucial role in capital structure decisions.

Why is this important?

Not because we live in M&M’s fantasy world where taxes, bankruptcy risks, and investor psychology don’t exist. But because at its core, the M&M theorem makes one crucial point:

A company's value is driven by two things:

Its ability to generate revenue.

The risk of the assets it uses to do so.

A firm’s capital structure? That’s just a tool. A company can tweak its debt and equity mix to optimize value (hello, tax shields), but no amount of financial engineering can fix bad fundamentals. If a business isn’t selling enough, or if its costs spiral out of control, no amount of capital structure magic will save it.

Other Theories

Of course, M&M’s assumptions were too rigid, and finance evolved. Several alternative theories emerged to fill the gaps:

The Trade-Off Theory: Companies balance the benefits of debt (tax shields) against the risks (bankruptcy costs) to find the “optimal” level of debt.

The Market Timing Theory: Firms issue equity when their stock is overvalued and take on debt when their shares are undervalued—making capital structure a game of market perception.

The Pecking Order Theory: Companies follow a financing hierarchy—first using retained earnings, then debt, and only as a last resort, equity issuance (since it’s the most expensive).

I won’t dive too deep into these today, but just know—capital structure isn’t as simple as M&M first proposed.

And about that pizza…

If you were wondering why I started with pizza, it wasn’t just for fun. Miller himself used a pizza analogy to explain his theory:

A pizza can be sliced in as many pieces as you want, but the total size stays the same. Similarly, a company’s capital structure might determine who gets which slice of the cash flows (debt holders vs. equity holders), but it doesn’t change the total cash flow pie itself—which ultimately determines firm value.

And with that, we wrap up this deep dive into M&M! Hopefully, you now see why capital structure matters—but only to a point. Thanks for sticking with me through this one—catch you next time!

📢 What do you think? Do you agree with M&M’s take on capital structure, or do you think real-world factors make their theory less relevant? Share your thoughts in the comments—I’d love to hear your perspective! 👇

🔔 Stay tuned! This Friday, we’ll dive into another fascinating finance topic (hint: it’s not about pizza this time 🍕). Subscribe now so you don’t miss it!

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

Our Recent Posts

What Trump’s Next Move Could Mean for Aris Investors

I’m not a huge fan of macroeconomics when it comes to investing.

Should You Sell Your Smartphoto Shares?

Today, we’re not going to talk about Aris – our latest hidden gem, which we found through a top-down analysis. Instead, we’re diving deep into a company that’s close to our hearts (and not just because our portfolio sits in our breast pocket).