“CDOs are like sausage. You might enjoy eating it, but you don’t necessarily want to know how it’s made.”

- Wall Street saying -

Welcome to Part II of our mini-series on the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). In Part I, we laid the groundwork — exploring the years leading up to the crash, the political, economic, and financial context that quietly built the perfect storm. If you haven’t read it yet, I recommend starting there for the full picture.

Now, let’s be clear: this isn’t about turning you into the next Warren Buffett (although hey, dream big). It’s not directly about investing skills either. But if you want to truly understand the world of finance — and why things sometimes go catastrophically wrong — then knowing what caused the GFC is a must. It sharpens your macro-economic lens, helps you connect the dots in today’s markets, and frankly, makes you sound pretty smart at dinner parties.

Today, we’re diving into two financial instruments that played crucial roles in the crisis: mortgages and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). They might sound a bit dry at first, but trust me — once you see how they were used (and abused), it becomes one of the wildest stories in financial history.

So, grab a coffee and let’s dive in!

Mortgages

Before we dive into the financial beast that played a starring role in the Great Financial Crisis, let’s rewind a bit and start with the basics: mortgages.

A mortgage is, quite simply, a loan backed by a house (or other property). It’s part of a broader asset class called “asset-backed securities” — which is finance-speak for “loans with stuff behind them.” The idea is straightforward: if the borrower stops paying, the bank can sell the house and (hopefully) get its money back. Think of it like a backup plan... an insurance policy that pays out in bricks and drywall.

Let me explain the risk of this setup by trading the house for something a little more... volatile. Recently, I stumbled across this gem of a project called “Fartcoin.” Yep. Fartcoin. A groundbreaking innovation in the world of flatulent finance. I’m telling you, if I don’t go all in right now, I’ll probably regret it for the rest of my life (just to be clear: this is (1) not financial advice and (2) absolutely dripping with sarcasm).

So let’s say I convince a bank to lend me money to invest in this, and I offer my precious stash of Fartcoin as collateral. If I default, no problem — they just sell my Fartcoin on the market and boom, they’ve got their money back, right?

Yeah... no. You see where this is going. The odds of Fartcoin being worth anything by the time the bank tries to cash in are about the same as me becoming the next Pope. And that’s the point: assets backing loans need to be relatively stable in value — or at least expected to go up. That’s what made real estate such a great candidate. At least, it used to be... until it wasn’t. (Cue ominous music.)

So, mortgages. There are two main types: fixed rate and adjustable rate. You’ve probably heard of both. But once upon a time — pre-1982 to be precise — there was only one flavor on the menu: fixed rate. Nice, simple, predictable. Then came the “Alternative Mortgage Transaction Parity Act” (aka AMTPA), and suddenly banks had the green light to roll out all kinds of fun, confusing loan structures. Loans with terms so complex, the average customer had no idea what they were signing up for. But hey, at least they were customized.

Anyway. Adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) were born, but we’ll come back to those. First, let’s focus on the OG: fixed rate mortgages.

Fixed Rate

With fixed rate mortgages, you pay the same amount each period. But — plot twist — that doesn’t mean you’re paying the same mix of interest and principal each time. Early on, most of your payment goes to interest. Later, it shifts more toward paying down the loan itself. In finance-nerd lingo, this setup is called an “annuity.”

But from the borrower’s perspective? No one really notices. You just send your money to the bank every month and hope they leave you alone.

To visualize how this breaks down over time, check out Image I. It's a €400,000 loan, paid off over 20 years at 3% interest.

That fixed bar across the top? That’s your total yearly payment. Inside the bar: the orange part is interest, the blue part is principal. The more you pay off, the less interest you owe, so more of your payment goes toward actually owning your home. See? Simple-ish.

Now, how much you pay in total — i.e., what your fixed rate is — depends on your credit score (hello, FICO score). Better score = lower interest = less total repayment. From the bank’s side, this is all about balancing risk and return. If you look sketchy on paper, they want more interest to make it worth their while. Simple math, really. But for you, it means higher monthly payments and a loan that takes longer to shrink. Check out Image II, same loan but at a spicy 10% interest rate:

Hold onto that idea — it’ll come in handy when we talk tranches later.

Adjustable Rate

Now, adjustable rate mortgages. These are similar in structure — still a loan, still secured by property — but with one major difference: the interest rate can change. (Gasp!)

Usually, your rate is based on a benchmark index (like the Fed rate in the US or the ECB rate in Europe), plus a “margin,” which is basically a risk surcharge. If you’re considered high-risk, your margin — and your rate — go up.

These loans often start with a teaser period of low, fixed interest — sounds great at first — before the rate starts floating. It’s re-evaluated regularly, and if the benchmark goes up… so does your monthly payment. That low fixed rate? Just bait. And a lot of borrowers, bless their optimistic hearts, didn’t fully understand what they were signing up for.

I won’t get too deep into how this impacts banks (we’re not turning this into Bankers 101), but for borrowers, the risk is crystal clear: if rates rise, your mortgage gets more expensive. Graph I (recycled from Part I) shows how that played out leading into the GFC. Central Banks started hiking rates... and well, we all know how that turned out…

Collateralized Debt Obligations

Now that we’ve wrapped our heads around mortgages, let’s level up. Eyes open, brains on, because this next financial Franken-product is where things start to get... well, stupid. And not in a fun, harmless way — more like how-did-anyone-think-this-was-okay stupid. This thing is the backbone of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). And once you see how deep the rabbit hole goes, there’s no going back. You’ve been warned.

If you’ve seen The Big Short (highly recommend — it’s Wall Street meets stand-up comedy meets existential dread), you might remember the Jenga tower scene. That’s the visual for what we’re about to unpack.

Let’s start with the name: Collateralized Debt Obligation, or CDO. Doesn’t sound too crazy yet, right? If we break it down, it’s actually pretty self-explanatory (which makes what happens next even more ridiculous).

Collateralized debt = debt backed by something tangible. Mortgages, car loans, student loans, whatever — as long as there’s some asset tied to it. These are known as asset-backed securities.

Obligation = just a fancy word for debt that investors can buy. Think of government bonds — you give them money now, they give it back later, with interest. A CDO is basically the same thing, but instead of lending to a government, you're investing in a bundle of loans to everyday people... who may or may not pay you back.

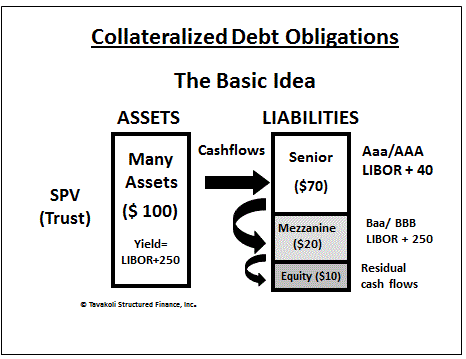

Now, here’s where the magic (read: chaos) begins. Banks don’t like holding onto risk. Shocker. So what do they do? They take all these loans people owe them, bundle them together into a neat little financial parcel, and sell it off to investors. Poof — risk transferred. The borrowers still make their payments, but now the money goes to the new investors via the bank. And since the whole thing is made of collateralized debt, we get... tada! A Collateralized Debt Obligation.

The most basic version? The CMO, or Collateralized Mortgage Obligation. It’s exactly what it says: a CDO made entirely of mortgage loans.

Still with me? Great. Now, let’s talk risk. Because not all loans are created equal. Banks love giving out ratings like they’re grading a high school math test. AAA? That’s the honor student. D? That kid hasn’t shown up to class all semester. Naturally, the riskier the loan (i.e., the worse the grade), the more return you get — assuming you actually get paid, that is.

So how do you deal with all this mixed-bag risk? Easy. You diversify — the golden rule of investing. Banks bundle a bunch of these loans together and slice them into different tranches (French for “slices,” because finance loves a little flair).

Senior tranches are the safest. They get first dibs on payments but earn the least. These are backed by your reliable, creditworthy borrowers.

Mezzanine tranches are the middle children. Not as safe, not as risky. They get paid next.

Equity tranches are the thrill-seekers. They take on the most risk, but if everything goes right, they rake in the most cash.

Here’s the kicker: if people start defaulting on their loans, the equity tranche gets wiped out first. Only if things get really bad do the mezzanine and senior tranches feel the pain. It’s a waterfall of doom.

Investors pick their tranche based on how much risk (and stomach acid) they can handle. Pension funds? They stick to the safe stuff — senior tranches. Hedge funds looking for big wins? Bring on the equity.

Now, these tranches don’t just magically assign themselves. That’s the job of the rating agencies — Moody’s, Fitch, and the ever-popular Standard & Poor’s (yep, that S&P). They’re the gatekeepers who slap a rating on each tranche, deciding who’s getting the AAA gold star and who’s sitting in the danger zone. Remember this — it’ll become very relevant later.

Alright, now for the plot twist. Someone — probably a banker who had one too many espressos and way too much time on their hands — thought: "You know what would be fun? Let’s take the senior tranche of CDO A, mix it with the senior tranche of CDO B, and make that the senior tranche of a brand new CDO."

Voilà: CDO-squared. It’s basically a CDO made up of other CDOs. Like financial inception. Sounds clever, right? Until you realize it’s just stacking risk on top of more risk and pretending it’s safer somehow. Spoiler: it wasn’t.

And yes, this actually happened. Wild, right?

The Next Steps

Next Friday, we’ll shift gears and take a closer look at the key players in this whole saga: the banks, the rating agencies, and good old-fashioned greed — arguably the real engine behind the crisis.

But before that, we’re taking a quick breather. On Sunday and Wednesday, we’ll temporarily step away from the GFC to dive into something a bit different: the financials of Aris Water Solutions. Then on Wednesday, we’ll cover a still-to-be-determined topic (ideas are always welcome — hit me with them).

For now, try to really grasp the mechanics and implications of these financial products. Because while they might seem abstract, things get very real, very fast when they go wrong — as history has shown us.

Thanks for reading this article – we honestly appreciate it – and see you on Sunday!

📢 What’s your take on mortgages, CDOs, or the insanity of CDO-squared? Drop a comment below — curious to hear what surprised you most.

🔔 Subscribe now so you definitely don’t miss the next part of this series — or any of the other deep dives we’ve got coming up.

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

Our Recent Posts

[Part II] Market Structures & Their Impact On Economic Moats

Before we jump into today’s topic, let’s do a quick recap of the key ideas from Part I. Ultimately, understanding market structures is about understanding how sustainable a company’s moat is—how well it can defend its competitive advantage over time. The type of market a company operates in plays a huge role in determining how hard (or easy) it is to ma…

Aris Financial Health Check

Alright, folks, we've spent weeks diving into the qualitative side of things—context, strategy, market positioning. But now, it's time to roll up our sleeves and get into the hard numbers. Because, let’s be honest, a company can spin a great story for investors, but does Aris actually have the financials to back it up? That’s what we’re here to find out.

![[Part II] Market Structures & Their Impact On Economic Moats](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0MTT!,w_280,h_280,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2601e39a-a3bf-4f93-974b-2feb58c693b4_1024x1024.png)