Finance is full of buzzwords and acronyms, but few concepts are as crucial—and as misunderstood—as the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). At its core, WACC is a blended estimate of the cost of equity and the cost of debt, rolled into a single number: the cost of capital. But why does this matter? Because it helps investors gauge the return they should expect relative to the risks they’re taking. These risks—typically market, country, and default risk—are baked into the WACC, though some, like liquidity risk, are often ignored under the assumption that most assets trade freely.

I don’t rely on WACC much these days, but wrapping my head around it was a key milestone in understanding the risk-return trade-off: the greater the risk (and therefore the cost of capital), the higher the expected return. This directly impacts how cash flows are discounted, a simple yet often overlooked relationship that leads us to today’s topic—Economic Value Added (EVA).

In this article, I’ll break down EVA: why it may (or may not) be useful, how to calculate it, and finally, I’ll walk you through a case study to bring it all to life. So, grab a coffee—it undoubtedly adds value to your day—and let’s dive in!

The Concept: EVA

Economic Value Added (EVA) was introduced back in 1991 by G. Bennett Stewart III—a name that doesn’t get much fancier than that. Stewart’s goal? To take traditional accounting statements and turn them into something actually useful for analysts and investors. His take on accounting was clear: “Accounting statements are useful for lenders, not owners.” In his view, they were too disconnected from reality, failing to reflect true value.

This brings us to two key questions:

What’s wrong with traditional accounting measures?

How can we tweak them to create a metric that’s actually meaningful for investors?

Let’s break them down one by one.

We’ve touched on this already in previous articles, but it comes down to the nature of accounting itself. Accounting follows strict principles that dictate which financial accounts are used (balance sheet, profit & loss) and when costs and revenues are recognized. The result? A mismatch between reported earnings and actual cash flow movements. And—as I titled a previous article—cash is king, so when we talk about shareholder value, we need to adjust for this.

Another issue? Accounting ignores opportunity cost. At the start of this discussion, I highlighted the importance of the cost of capital, which is, at its core, an opportunity cost. It answers a simple but crucial question:

"How much return should I expect from an alternative investment?"

Since this isn’t a real cost (in the sense that no cash physically leaves the business), it’s completely left out of financial statements. I get it—this might sound like it contradicts the whole “cash is king” mantra. But stick with me.

In a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, we estimate future cash flows, but then we discount them back to their present value. This discounting process is what accounts for opportunity cost. Bottom line? If we want a measure that truly reflects economic value, we need two key corrections:

Adjust for actual cash flows.

Factor in the opportunity cost of capital.

That’s exactly what EVA does.

The EVA Formula

EVA = NOPAT – (r × Invested Capital)

Where:

r = opportunity cost (either the cost of capital or a chosen hurdle rate).

r × Invested Capital = essentially the finance cost of the investment.

Rewriting it gives us a clearer view of EVA’s drivers:

EVA = Sales – Operational Costs – (r × Invested Capital)

So, EVA increases when:

Sales go up → sales growth drives value.

Operational costs go down → efficiency drives value.

Opportunity cost (r) is lower → cost of capital matters.

Invested capital is lower → capital efficiency matters.

At first glance, this confirms what we already know: growth and efficiency drive Economic Value Added. But there’s more. The opportunity cost component means that just breaking even operationally isn’t enough anymore. There’s a new benchmark—one that considers alternative investment opportunities in the market. That’s what makes EVA so powerful for shareholders.

Let’s rewrite the formula one last time to uncover another key insight:

EVA = (ROIC × Invested Capital) – (r × Invested Capital)

= (ROIC – r) × Invested Capital

If you’re wondering where the magic happened—pay attention. NOPAT can be rewritten as ROIC × Invested Capital, and thanks to the distributive property in math (yes, I had to look that up too), we get this final equation.

What does this mean in plain English?

Invested Capital can’t change the sign of EVA—it only scales it.

If ROIC > r, EVA is positive (value is created).

If ROIC < r, EVA is negative (value is destroyed).

It all boils down to a simple truth: if a firm’s return on invested capital exceeds its cost of capital, it creates value. If not, it doesn’t.

Easy. But not simple.

A Case Study

Let’s put this theory to work. As an example, we’ll once again take Melexis, our beloved semiconductor designer. But instead of using EVA to forecast performance, we’ll use it to evaluate past results. Of course, EVA can also be a powerful tool when running a DCF analysis, helping estimate how much economic value an asset adds based on your assumptions.

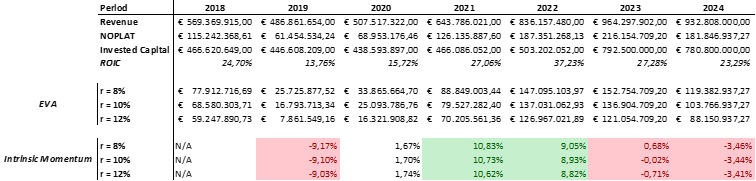

For simplicity, I assumed that Invested Capital at the end of year t-1 equals the Invested Capital at the beginning of year t, adjusted for reinvestments. An example in plain English: the Invested Capital at the end of 2022 is the same as the Invested Capital at the start of 2023, minus the reinvestments made during 2023. This method isn’t perfect, and minor deviations may occur, but it works well enough for illustrative purposes.

Now, let’s look at the numbers. The EVA is consistently positive, meaning Melexis has been a value-creating company over the past few years. This is further backed by its ROIC consistently exceeding the assumed opportunity cost (whether 8%, 10%, or 12%).

EVA Margin

So, exercise complete? Not so fast. Mister Stewart had a few more tricks up his sleeve. While EVA is useful, it’s just a raw number—it doesn’t tell us much on its own. Is $50 million a lot? Or not so much in this context?

To get a clearer picture, we scale EVA against the company’s sales, giving us the EVA Margin. This is a much more insightful metric, showing how much value the company creates relative to its own revenue. Let’s take a look at Melexis and see how it stacks up against some benchmarks.

A few things pop out immediately:

✔ Green numbers (EVA Margin > 12%) = excellent performance.

✔ The lower the opportunity cost (r), the higher the EVA Margin. No surprises there—lower capital costs mean more value creation.

✔ When r = 12%, EVA Margin plunges once to 1.6%, slipping below the 3% "low EVA" threshold—a red flag.

This also highlights a crucial point: numbers alone aren’t enough—you need a solid narrative. Without a clear rationale for choosing an opportunity cost, it’s easy to manipulate EVA to fit whatever story you want.

Scenario 1 (r = 8%)? Melexis looks like a no-brainer buy.

Scenario 3 (r = 12%)? You might want to sleep on that decision.

Same company, same data—just a different cost of capital. That’s the power (and the danger) of assumptions.

Intrinsic Momentum

Lastly, let’s introduce Intrinsic Momentum (IM)—a measure that captures how much EVA is changing, scaled against the prior year’s sales. Time for a quick demonstration:

Unlike EVA and EVA Margin, IM smooths out the distortions caused by different opportunity costs. Since it measures change rather than absolute value, it’s less sensitive to scaling issues. But there's a trade-off—IM is far more volatile.

Good years → Huge spikes

Bad years → Sharp drops

This volatility makes sense: when a company transitions from bad to good performance (or vice versa), the EVA change is dramatic.

Each of these three measures—EVA, EVA Margin, and Intrinsic Momentum—captures a different piece of the puzzle. Using them together gives the best picture of a company’s true value-creating potential. And the best part? EVA is incredibly easy to calculate. No complex models, no 100-line Excel sheets—just three key numbers, and you’re ready to go.

That said, be cautious when comparing EVA across companies, especially across industries.

Capital-intensive vs. capital-light businesses? Huge differences in EVA drivers.

Mature vs. high-growth markets? EVA dynamics shift dramatically.

For the best comparison, find a peer company with similar operational characteristics.

Hopefully, this case study made these otherwise abstract formulas feel a bit more tangible.

Final Remarks

EVA is a powerful tool—it refines traditional accounting measures, integrates opportunity cost, and provides a clearer view of a company's true value creation. But like any financial metric, it comes with trade-offs that investors need to consider.

1. The Simplicity vs. Assumption Trade-off

One of EVA’s greatest strengths is its simplicity—three key inputs (NOPAT, Invested Capital, and Cost of Capital) are all you need. No massive spreadsheets, no overcomplicated models. However, this simplicity is a double-edged sword. EVA is only as good as the assumptions behind it—especially the opportunity cost of capital (r). A small change in r can dramatically shift the results, making a company look like either a golden investment or a value destroyer.

Takeaway: Don’t just take EVA at face value—always question the assumptions behind it.

2. Absolute vs. Relative Interpretation

A raw EVA number tells you whether a company is creating value, but not how much value it creates compared to its size. This is why EVA Margin is so useful—it puts EVA into context by scaling it against sales. Similarly, Intrinsic Momentum (IM) helps filter out distortions caused by changes in the cost of capital, making it a strong tool for tracking value creation over time.

Takeaway: Use EVA alongside EVA Margin and IM to get a complete picture of a firm’s performance.

3. Industry and Market Context Matters

EVA is great for comparing companies within the same industry, but it doesn’t travel well across sectors. A capital-intensive business (e.g., airlines, telecom) will naturally have lower EVA than an asset-light tech company. Similarly, a mature market company won’t generate the same EVA growth as one in a high-growth sector.

Takeaway: Always compare EVA against industry peers, not across vastly different business models.

At the end of the day, EVA isn’t a silver bullet—it’s a tool. And like any tool, it’s only as useful as the person using it. It can highlight where value is being created (or destroyed), but it can’t tell you why. That’s where analysis, business fundamentals, and a clear investment thesis come in.

So, use EVA wisely. Challenge your assumptions. Compare within the right context. And most importantly—don’t let the numbers fool you into thinking finance is ever truly straightforward.

📢 What’s your take? EVA flips the script on traditional financial metrics, but no model is perfect. Do you think there’s a better way to measure value creation? Let’s hear your perspective—drop a comment and let’s discuss! 👇

🔔 Don’t miss out! This Sunday, we’re kicking off our deep dive into Aris Water Solutions—breaking down the numbers, the strategy, and what it all means for investors. Stay tuned!

Please note: This article includes a disclaimer regarding investment advice.

References

https://www.evadimensions.com/

Our Recent Posts

AI-tisation. A View On The Future Of AI.

“Great. Another opinion on AI. Just what I needed.” I can practically hear you thinking it. And honestly? I’d probably have the same reaction.

Are Small Caps the Ultimate Contrarian Bet?

For quite some time now, I've been hearing the same message here in Belgium: "Now is the time to invest in small caps." It’s a phrase that keeps coming up in investment circles, financial discussions, and even casual conversations among investors. But as any seasoned investor knows, hype alone isn’t a reason to jump in. So, I decided to dig deeper.

Are Financial Decisions Actually Made by Animal Spirits?

Subscribe now to receive our updates directly in your inbox!